In a country terrorized by gangsters, it is left to the dead to break the silence on violence.

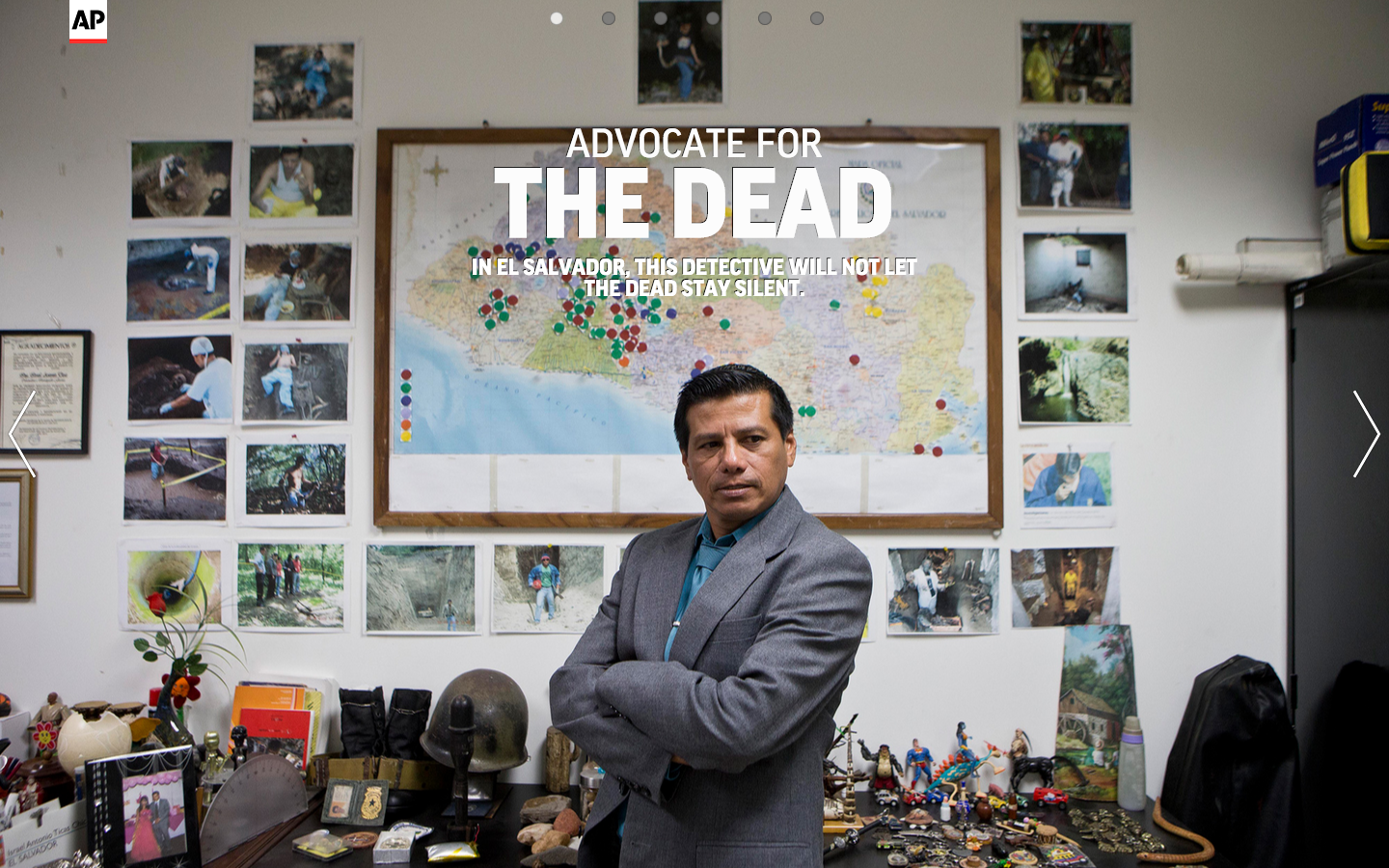

Multimedia portrait of fascinating criminologist Israel Ticas, who leads the teams that search for bodies still missing from a decades-old civil war, and for those killed more recently by street gangs who hold most of El Salvador in their clutches.

To see the full interactive please click link below:

SYNOPSIS/

Ticas calls himself the “lawyer for the dead.” In fact, he is a systems engineer turned police detective who taught himself forensic science. Most people call him Engineer.

Short and solidly built, he looks younger than his 51 years. Ticas speaks in the street slang of the gangsters who occupy his neighborhood, but looks the part of a plainclothes cop. When not in biohazard gear, he wears a leather jacket and dark glasses, or a double-breasted suit with a tie held in place by a gold clip.

He was a young police intelligence agent during the US-backed government’s war against Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front guerrillas in the 1980s. Today, those former guerrillas hold the presidency, and Ticas works for an independently named attorney general as the department’s only criminologist.

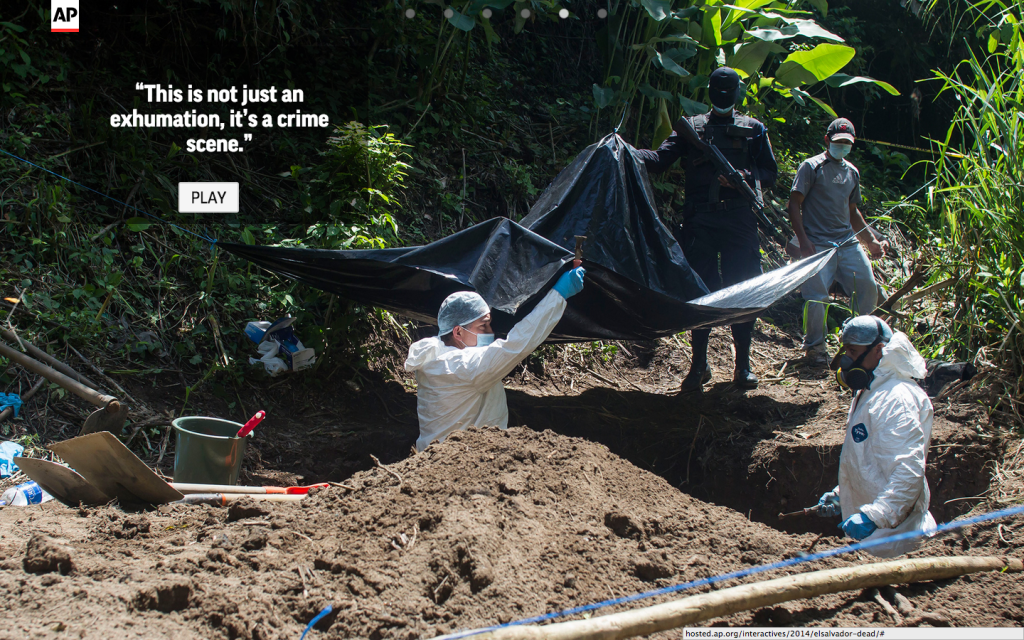

Some would argue that digging up the dead is a fool’s errand in El Salvador, which has the world’s second highest per capita homicide rate after neighboring Honduras, and where the slightest offense can lead to death. Ticas knows this better than anyone as he sees the evidence of gang rape and sadistic methods of murder such as “the pinata,” where a victim is hung upside down from a tree and hacked to death with machetes, like children batting a candy-filled piñata.

He considers all killers to be devils, no matter their affiliation. He calls himself a lawyer because he seeks justice for the dead, whoever they might be and whoever may have killed them. It so happens that gangs are doing the lion’s share of killing to enforce their control, and going to great lengths to conceal the dead, many of them women and discarded girlfriends.

He calculates that in the last 12 years he has opened about 90 common graves with more than 700 bodies, about 60% of them women and girls. That is a fraction of what’s out there, he believes, but Ticas does not have the time or staff to find all of them.

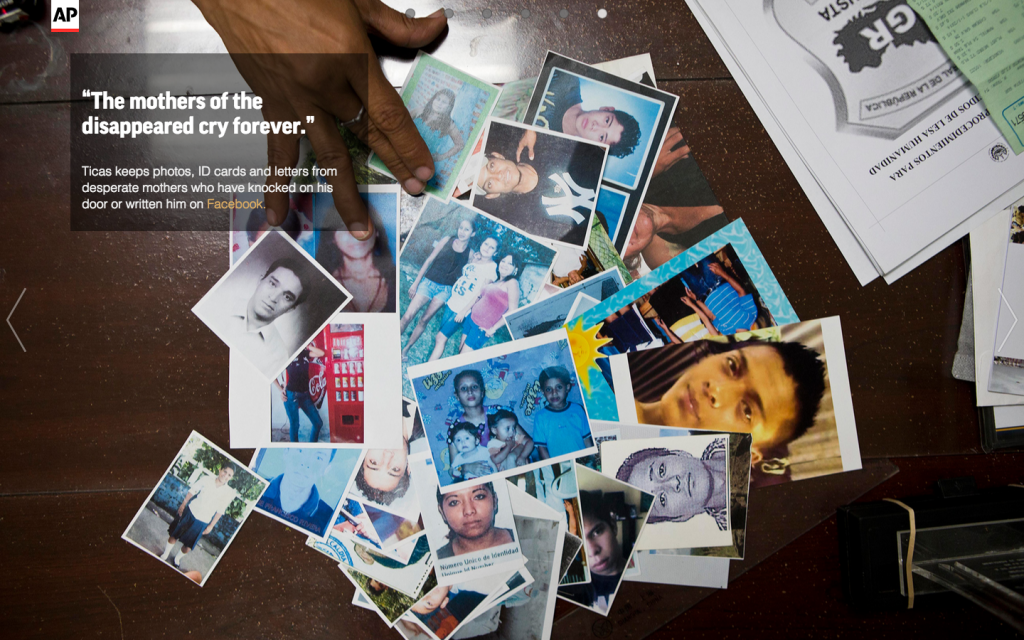

The number of missing in El Salvador is a subject of debate, with estimates ranging from 600 to 2,000 per year. Many of those reported missing may well have fled to the United States, while the disappearance of many other Salvadorans goes unreported out of fear of the gangs.

But that doesn’t mean families aren’t looking. Ticas pulls a metal box out of his desk stuffed with photographs, identity documents and letters from desperate mothers who come knocking on his door at all hours of day and night.

“‘Is this where Israel Ticas lives, the one who looks for the dead?’ they ask. ‘Look, they disappeared my daughter and I need to find her even if she’s dead,’” Ticas recounts.

And then he adds without affect, “I get scared because I realize the whole world knows where I live.”

CREDITS/

Interactive Alba Mora Roca

Photos Esteban Félix Salvador Meléndez

Video Alba Mora Roca

Reporting Alberto Arce

Published December 19th, 2014